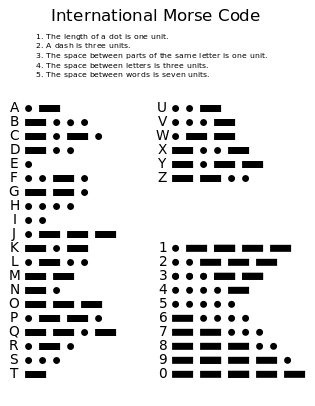

In 1836, Samuel Morse and others founded this way of communication using dots and dashes as a quick way to get a message across. The signal strength never mattered too much because it would use so little strength to get the message across. As along as the person receiving it could understand the message things usually went smoothly. As voice transmission made its way into control, Morse code became a background player. It was the alternative way to send a message if the voice transmitters had not enough signal strength or were just not functional.

Soon after the rise of Morse code it had been incorporated into a lot of ship equipment. Many of the communication receivers we have here at, the Museum of Maritime navigation and communication, were used to pick up these signals. The early distress equipment such as the EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) and the Lifeboat Radiotelegraph Transmitter- receiver, functioned with Morse code as a center point. Morse code was a universal and easy way to transmit distress and problems aboard ships. These devices would transmit on frequencies both on land and in the sky. Pilots would be able to hear forms of distress if in the vicinity of a sinking vessel or a vessel in trouble. Most pilots and air traffic controllers had basic understandings of the system, enough to ensure the action needed when distress echoed on the frequencies. Many radio repeaters can identify with Morse code even though voice communications dominate the skies.

Morse code has since decreased in popularity since the start of the 21stcentury it is still a very interesting form of communication. Schedule a tour with us and even get hands on experience with our Morse code exhibit.

Visit our website at mmncny.org, tweet us at @mmncny or even check out the current Morse code exhibit we have ongoing now at the Staten Island Children’s Museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment